Purdue professor studies the pain of ostracism

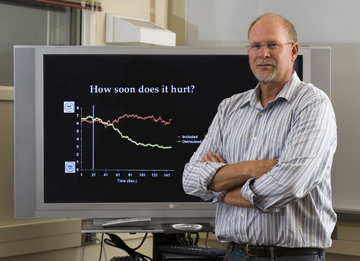

Kip Williams' research has shown that just as ostracism is quickly adaptive, so too is an individual's detection of it. Williams is a professor of psychological sciences at Purdue. (Purdue University photo/Mark Simons)

Since seeing a documentary on the subject in the late 1970s, Kip Williams has been interested in ostracism, the act of ignoring or excluding, and its sometimes tragic consequences. But it took a personal incident in the park for this professor of psychological sciences to realize how to test it on subjects in a lab setting.

When it comes to ostracism, Williams says, we're like pedestrians and drivers. "Whichever side you're on," he says, "you don't have much sympathy for the other group."

Anyone who has ever received the silent treatment from a spouse or friend, classmate or co-worker, knows well the pain the act instills. In the animal kingdom, ostracism of an individual monkey, lion or tiger means almost certain death. And Williams says evolutionary psychologists believe that it appears to be adaptive for all social animals to free themselves of burdensome members.

But what of ostracism and the abandoned individual in human social circles?

"With humans, we learn to use ostracism whenever we want to punish someone, whether they're a burden or not," says Williams, whose research has shown that just as ostracism is quickly adaptive, so too is an individual's detection of it.

Williams found his research subject matter through a documentary about a West Point cadet named James Pelosi, ostracized for two-and-a-half years by his classmates for finishing a sentence instead of putting his pencil down on a test. "I was fascinated by the power of a non-behavior," he says. "His roommate moved out. No one talked to him or looked at him. If he sat down at a table to eat, everyone at the table would leave. It seemed to be more powerful than anything else."

For Williams, an otherwise ordinary day in the park with his dog led him to his research method in 1994. After a Frisbee fell at his feet, Williams tossed it back to one of the throwers, who then fired it back to him. This happened a couple more times until Williams found himself in the middle of a triangle toss. But then, just as suddenly, the other two guys stopped throwing him the disc. Realizing his exclusion, Williams returned to his canine.

"I was surprised how bad I felt," say Williams, who recovered quickly, in part, when he realized the research applications of the incident.

Fast-forward some 15 to 16 years and Williams can share a collection of documented experiences on the effects of being eliminated from a game of toss. These days, subjects are invited to a virtual game of "Cyberball." After one or two ball tosses from an anonymous computer icon, the player is excluded.

"Even in a virtual setting, it's enough to make a person feel really bad," Williams says.

One video of a Cyberball player shows his emotional range when quickly excluded from toss -- from humor (laughing) to anger (a one-finger gesture) to an obvious expression of dejection.

Williams has concluded that ostracism's detection is a hard-wired response. And he says it doesn't matter even you're being ignored by a group you despise, such as the Ku Klux Klan. The pain still registers. In fact, through the use of MRIs, research shows the same brain receptors that measure physical pain light up as a subject is ignored.

So what's the point of pointing out this pain?

"At one level we know how much it hurts people," Williams says, "but we may not realize how damaging it can be. Long-term sufferers can become alienated, clinically depressed, even suicidal."

With few exceptions, we’ve all been on either side of the ostracism fence, Williams says. It's the reaction, usually in the reflective mode away from the exclusion incident, that's reflective of differences in mental makeup. He says the default reaction when ostracized is literally to regroup -- become more socially aware, work on self-improvement, even find new friends. In extreme cases though, those ostracized, threatened by a sense of belonging and believing positive relationships are no longer an option, may lash out violently.