October 19, 2004

'Knowledge discovery' could speed creation of new products

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – In the recent science-fiction thriller "Minority Report," Tom Cruise plays a detective who solves future crimes by being immersed in a "data cave," where he rapidly accesses all the relevant information about the identity, location and associates of the potential victim.

|

A team at Purdue University currently is developing a similar "data-rich" environment for scientific discovery that uses high-performance computing and artificial intelligence software to display information and interact with researchers in the language of their specific disciplines.

"If you were a chemist, you could walk right up to this display and move molecules and atoms around to see how the changes would affect a formulation or a material's properties," said James Caruthers, a professor of chemical engineering at Purdue.

The method represents a fundamental shift from more conventional techniques in computer-aided scientific discovery.

|

"Most current approaches to computer-aided discovery center on mining data in a process that assumes there is a nugget of gold that needs to be found in a sea of irrelevant information," Caruthers said. "This data-mining approach is appropriate for some scientific discovery problems, but scientific understanding often proceeds through a different method, a 'knowledge discovery' approach.

"Instead of mining for a nugget of gold, knowledge discovery is more like sifting through a warehouse filled with small gears, levers, etc., none of which is particularly valuable by itself. After appropriate assembly, however, a Rolex watch emerges from the disparate parts."

A team of researchers at Purdue led by Caruthers is developing a computer environment that allows experts to talk naturally in their specific scientific language. That way, the researchers don't have to deal with computerese and can take full advantage of the most advanced visualization capabilities to become more engaged in the scientific discovery process, Caruthers said.

Such a system could become crucial for enabling scientists to deal with the recent explosion of data now available to them. The source of this flood of data is "high-throughput" experimentation, in which hundreds or thousands of experiments are conducted simultaneously in tiny vessels that are sometimes as small as a few human hairs. Having so much information presents a challenge: it is difficult for researchers to find what they are looking for within this huge sea of data.

"You run the risk of drowning in data," said W. Nicholas Delgass, a Purdue professor of chemical engineering. "What you really want is knowledge, not data."

Purdue researchers believe they have a solution to the problem. They are developing a method to extract knowledge from data, promising to speed up the process of discovery in many areas of research, including work aimed at creating new drugs, fuel additives, catalysts and rubber compounds.

The method, called "discovery informatics," enables researchers to test new theories on the fly and literally see how well their concepts might work in real time via a three-dimensional display, said Venkat Venkatasubramanian, another professor of chemical engineering working to develop the new system.

The multidisciplinary effort involves researchers from Purdue's College of Engineering, School of Science, School of Technology, Information Technology at Purdue, or ITaP, and the e-Enterprise Center in Purdue's Discovery Park, a collection of six centers formed to speed the development of new technologies.

Discovery informatics depends on a two-part repeating cycle made up of a "forward model" and an "inverse process" and two types of artificial intelligence software: hybrid neural networks and genetic algorithms.

The forward model combines fundamental knowledge and rules of thumb with neural networks – software that mimics how the human brain thinks – to tell researchers how a particular material will perform.

"In the forward model, a researcher postulates a molecular structure or a product's formulation and then wants to predict what properties that structure or formulation will have," Delgass said.

The inverse process is just the opposite: Researchers enter the properties they are looking for, and the system gives them a molecular structure or formulation that will likely have those properties. The inverse process cannot begin until the forward model is completed because the former depends on information in the model.

"What we are talking about is an advanced method for product design," said Venkatasubramanian. "The product design problem is this: I want some material that would have the following mechanical, chemical, electrical properties and so on.

"I know what properties I want in order to get my job done, but I don't know what material, what molecular combinations, will give me that. It is a bit like 'Jeopardy.' You know the answer, but you are looking for the question."

The inverse process may use genetic algorithms, software programs that mimic the Darwinian survival-of-the-fittest evolutionary approach to find the best candidates. The algorithms cull the best materials and eliminate the poor performers, just like survival of the fittest, generating "mutations" of the best materials to create even better versions over time, and the software determines the chemical structures of those mutations.

The resulting formulas are tested and used to improve the forward model, and the cycle starts over again, progressively creating better and better solutions.

"Once we have the forward model, we use it to predict which possibilities are going to be good," Delgass said. "Many of them turn out to be bad, but all of the negative information essentially tells me that the model has a flaw because it initially said these were good possibilities, and they weren't.

"Now that I have an opportunity to fix the model, I have a repeating way of making the model better and better."

The cycle might be called a "forward-inverse loop," a method for creating mathematical models that are critical to the discovery process.

"Before you can create one of these models, you typically spend years discovering the fundamental scientific principles behind the problem," Caruthers said. "We want to drastically speed up that discovery process, so that it no longer takes years to create models for important industrial products and processes."

Before high-throughput experimentation, researchers were able to keep up with the amount of available data.

"It's a little bit like horse-and-buggy transportation 100 years ago in this country," said Venkatasubramanian. "The horse and buggy did 10 miles per hour, and your country road supported 10 miles per hour, so everyone was happy. But suddenly now you can produce a month's worth of data in a matter of hours via high-throughput experiments. It's like having a Ferrari on a country road. You can do 200 miles per hour, but you are still stuck driving on the country road.

"Now we need an interstate, a modeling superhighway."

Discovery informatics, which has numerous potential applications, is that modeling superhighway.

"The opportunities are enormous for engineers who work in product design, which is now largely done as an art form by formulation chemists," Caruthers said. "We want to retain the creative aspects that can only come from the human mind, while reducing the amount of guesswork now needed to create new catalysts and other materials.

"Researchers generally discover with an Edisonian, guess-and-test approach. Lots of intuition. Lots of experience. Lots of gray hair. And a little bit of luck. But that cycle is too long, too expensive."

With conventional methods, it might take several years and thousands of tests before hitting on the right formulation, whereas discovery informatics dramatically speeds up the process by using a computer to sample potential materials and requires a fraction of the usual number of laboratory experiments.

The method will be tested in a new Center for Catalyst Design headed by Delgass and funded with a three-year, $2.4 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy and $1.7 million from the Indiana 21st Century Research and Technology Fund, established by the state to promote high-tech research and to help commercialize university innovations.

Catalysts in American industry account for billions of dollars in annual business revenues. That means even small improvements in catalyst performance can result in significant increases in profits, Delgass said.

Discovery informatics uses the scientific method to enable researchers to test new theories and hypotheses.

"In the scientific method, you make a hypothesis, you see whether the hypothesis fits the data – it never does the first time," Caruthers said. "You then revise your hypothesis and test it back against the data. It's a little better, but it isn't right. You do it again, and you do it again, and eventually you get to where your data and your hypothesis match, and you say, 'Now I have knowledge.'"

Researchers in Purdue's e-Enterprise Center helped the chemical engineers create software prototypes needed to manage huge amounts of data and simulations, turning the information into interactive images, said Joseph Pekny, director of the e-Enterprise Center and a professor of chemical engineering.

Then information technology experts use supercomputers to run the complex software for applications such as predicting chemical reactions and then "visualizing" such data on a three-dimensional, 12-foot-wide, 7-foot-high display in the Envision Center, said Gary Bertoline, associate vice president for discovery resources at ITaP and a professor of computer graphics technology in Purdue's School of Technology.

"We are helping them look at large amounts of data all at the same time," said Laura Arns, a visualization and computer graphics application engineer at ITaP. "You can display information in stereo, in which the left and the right eye each get their own pictures, and you get a 3-D depth effect. To see the 3-D visualization, you wear special glasses that are like sun glasses."

A large 3-D high-resolution display, known as a tiled wall, allows researchers to look at an entire problem, including chemical and atomic structures, graphs and charts.

"You are no longer limited to the size of a computer screen," Caruthers said. "You now have a huge field of view."

Caruthers likens the display to the concept moviegoers saw in "Minority Report."

"We're almost there," Caruthers said. "We will soon have a sophisticated tool that shows researchers in real time whether a particular idea is on the right track."

The method allows scientists and engineers to take full advantage of human creativity.

"Discovery requires human beings making intuitive leaps," Caruthers said. "You try one thing. It doesn't work, you try something else. Sometimes you go off in an entirely new direction.

"But this process is very inefficient. What we are doing is enhancing the efficiency of this process, assisting the intuitive human mind by providing massive data and computing power."

The three engineers presented a paper about their method in July during an international conference, Foundations of Computer-Aided Process Design, at Princeton University. Purdue held a workshop on Sept 13 and 14 focusing on methods of visualizing and manipulating data for the design of new catalysts for chemical reactions. The workshop attracted representatives from national laboratories, industry, academia and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Work to develop the method began in 1988 with funding from the National Science Foundation. Further research has been funded by Lubrizol Co., the Indiana 21st Century Research and Technology Fund and Caterpillar Inc.

Writer: Emil Venere, (765) 494-4709, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: James M. Caruthers, (765) 494-6625, caruther@ecn.purdue.edu

W. Nicholas Delgass, (765) 494-4059, delgass@ecn.purdue.edu

Venkat Venkatasubramanian, (765) 494-0734, venkat@ecn.purdue.edu,

Gary Bertoline, (765) 494-0541, bertoline@purdue.edu

Laura Arns, (765)494-6432, arns@purdue.edu

Joseph Pekny, (765) 494-3153, pekny@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Note to Journalists: A hard copy or electronic version of the research paper is available from Emil Venere, (765) 494-4709, venere@purdue.edu.

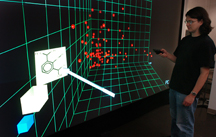

PHOTO CAPTION:

Purdue University graduate student Leif Delgass reviews chemical structures associated with points in a 3-D "scatter plot." The interactive graph is part of a system being developed at Purdue University that could dramatically speed up scientific discovery by enabling researchers to test hypotheses in real time using high-performance computing and artificial intelligence software.

(Purdue News Service photo/David Umberger)

A publication-quality photograph is available at https://ftp.purdue.edu/pub/uns/+2004/caruthers-informatics.jpg

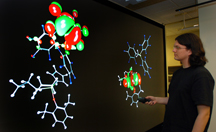

PHOTO CAPTION:

Purdue University graduate student Leif Delgass reviews "molecular orbitals" of a catalyst containing titanium as it is being used to make a plastic polymer, such as polyethylene. The interactive display is part of a system being developed at Purdue University that could dramatically speed up scientific discovery by enabling researchers to test hypotheses in real time using high-performance computing and artificial intelligence software.

(Purdue News Service photo/David Umberger)

A publication-quality photograph is available at https://ftp.purdue.edu/pub/uns/+2004/caruthers-informatics2.jpg

Discovery Informatics:

A Model-Driven Multi-Scale Integrated Framework

for Product Design and Engineering

W. Nicholas Delgass

Center for Catalyst Design

School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University

Designing new materials and formulations with desired properties is an important and challenging problem, encompassing a wide variety of products. Traditional trial-and-error design approaches are laborious and expensive, delay time-to-market, and miss some potential solutions. Furthermore, the growing avalanche of high throughput experimentation data has created both a opportunity and a major informatics challenge for materials design and discovery. However, we cannot use experimental data alone to "find" new materials, as we must have knowledge to guide the search more effectively. A new paradigm is needed that increases the generation of potential leads significantly, broadens the search horizon, and extracts knowledge from today's successes and failures in order to accelerate the discovery of new products tomorrow. Towards this end, over the past decade we have been developing a novel model-based, multi-scale integrated methodology called Discovery Informatics. This framework enables the management of large complex data sets, systematic extraction and accumulation of knowledge, iterative model refinement via hypotheses testing by interaction with experiments, and efficient search for new materials with desired performance characteristics. This paradigm has two main components: a forward model connecting descriptors of material structure or formulation to performance and an inverse process to determine optimal material structure or formulation from desired performance. While a rigorous first-principles forward model is desirable, a totally fundamental approach is often not practical. Therefore, a hybrid approach is adopted, where one can guide convergence to an increasingly fundamental model in concert with an information-rich data flow. Such a hybrid model combines fundamental knowledge, expert rules and statistical correlations of experimental data. We have developed an enabling intelligent modeling system – Reaction Modeling Suite that aids the human expert in building kinetic forward models facilitating knowledge extraction. Once a robust forward model is available, the inverse problem is addressed using evolutionary algorithms that exploit system knowledge to efficiently search the combinatorial space for materials matching performance targets. We will present the application of this paradigm on three widely different industrial product design domains: fuel-additives design, sulfur-vulcanized elastomers formulation and catalyst design.

To the News Service home page