July 1, 2005

Techniques available to detect soil that inhibits destructive soybean pest

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Identification of soils that inhibit a tiny soybean-destroying organism is an important tool in reducing yield losses, according to a Purdue University plant pathologist.

|

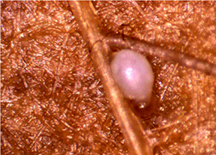

Soybean cyst nematodes cause between $800 million and $1 billion annually in crop losses in the United States, according the American Phytopathological Society. However, techniques are available to find soils that specifically suppress these microscopic roundworms, said Andreas Westphal, assistant professor of plant pathology. The female nematodes are white, lemon-shaped parasites that become dead brown shells filled with maturing eggs. Some soils have as yet not-understood characteristics that don't foster development of the pests.

Westphal, whose research focuses on soybean cyst nematodes and ways to thwart them, said that using nematode-suppressive soils is an environmentally friendly weapon in fighting the parasites, which are found worldwide in soybean-producing areas.

"Using plants bred to resist pests is not the complete answer, so it's important to find suppressive mechanisms," Westphal said. "Bio-control is much more desirable than using chemicals in order to limit damage to the environment."

In a paper published in the just-released March 2005 issue of the Journal of Nematology, Westphal summarizes the techniques for identifying soil that specifically suppresses soybean cyst nematodes. He also discusses how to use nematode-suppressive soils to battle the root-dwelling pests and the limitations of the techniques.

In previous research on a different cyst nematode, Westphal and his colleagues determined that mixing 1 percent to 10 percent of nematode-suppressive soil into the top layer of a soybean field plot effectively decreased nematode activity. In addition, they know that viability of plants and soil richness, moisture and temperature can affect how active and numerous soybean cyst nematodes are in particular fields.

"A key find was that a small amount of suppressive soil or a cyst from a suppressive soil can lower nematode numbers," Westphal said. "We promote conditions in soil to suppress the nematode, and we also study the soil so that we can determine the mechanisms that create suppression."

Some types of fungi and other organisms help keep the soil healthy by feeding on nematodes. Whether a field is tilled can affect nematode population density, but it's not yet known whether this is related to a change in the number of nematode-eating microbes, Westphal said. Further study is needed on how microbial communities function in order to determine conditions that contribute to nematode development.

Westphal was able to confirm the nematode supressiveness of soil by using treatments to eliminate soil organisms and other elements that inhibit nematode development. Another confirmation technique was to add suppressive soil to soils conducive to nematode development. The researchers also were able to document reduced nematode reproduction, population density, and whether certain types of soil were suppressive to specific pathogens.

"Currently, we are extending this research to finding ways to create more nematode suppression in soil," Westphal said. "This is important because nematode populations constantly change so they can overcome certain types of resistance, including even plants that are bred to be resistant to the organisms."

Westphal and his research team conducted a survey throughout Indiana to locate nematode-suppressive soils in an effort to make this tool more available and to further study the mechanisms that create its effectiveness against the pathogen.

Soybean cyst nematodes, one of a large, diverse group of multicellular organisms, are the most destructive soybean pathogen in the United States. The nematodes were first documented in Japan in the early 20th century and first reported in the United States in 1954. However, evolutionary biologists believe the pests were probably present in both areas as much as thousands of years earlier.

The females of the species use a short, hypodermic needle-like mouth to pierce soybean roots and suck out the nutrients. As the adult female ages, she fills with eggs, turns yellow and then brown to become the nematode cyst. At that point her body is a case to protect hundreds of eggs while they mature, hatch into juveniles and leave the cyst to further attack the plant roots. Swollen females can be seen with the naked eye, but worm-like juveniles and males can best be seen with a microscope.

As nematodes steal nutrients from the roots, the plants are weakened and don't grow well. Subsequently, plants may be more vulnerable to attack by other stresses, such as insects, diseases and drought.

It's often impossible to see symptoms of soybean cyst nematode damage, so soil and roots must be tested to reveal or confirm the pests' presence. Infestation gradually causes progressively lower yields and the worst cases result in yellow and stunted soybean plants. Plants with severe, visible damage can occur in patches in highly infested fields.

There are no pesticides that will eradicate soybean cyst nematode, which also preys on other legumes and some grasses.

The United States Department of Agriculture is providing funding for Westphal's study of the soybean cyst nematode.

Writer: Susan A. Steeves, (765) 496-7481, ssteeves@purdue.edu

Source: Andreas Westphal, (765) 496-2170, westphal@purdue.edu

Ag Communications: (765) 494-2722;

Beth Forbes, forbes@purdue.edu

Agriculture News Page

Note to Journalists: Contact Susan A. Steeves, 765-494-7481, ssteeves@purdue.edu for a copy of the study.

Related Web sites:

Society of Nematologists

USDA-Agriculture Research Service Plant Diseases National Program

PHOTO CAPTION:

A female sugar beet cyst nematode, which is similar to a soybean cyst nematode, is white when filled with eggs. The nematodes turn brown as their bodies become cysts harboring the eggs that hatch into juveniles, which continue the cycle of stealing nutrients from the plants. (Photo/Andreas Westphal, Purdue University)

A publication-quality photo is available at https://www.purdue.edu/uns/images/+2005/westphal.nematode.jpg

Detection and Description of Soils

with Specific Nematode Suppressiveness

Soils with specific suppressiveness to plant-parasitic nematodes are of interest to define the mechanisms that regulate population density. Suppressive soils prevent nematodes from establishing, from causing disease, or they diminish disease severity after initial nematode damage in continuous culturing of a host. A range of non-specific and specific soil treatments, followed by infestation with a target nematode, have been employed to identify nematode suppressive soils. Biocidal treatments, soil transfer tests, and baiting approaches together with observations of the plant-parasitic nematode in the root zone of susceptible host plants have improved the understanding of nematode-suppressive soils. Techniques to demonstrate specific soil suppressiveness against plant-parasitic nematodes are compared in this review. The overlap of studies on soil suppressiveness with recent advances in soil health and quality is briefly discussed. The emphasis is on methods (or criteria) used to detect and identify soils that maintain specific soil suppressiveness to plant-parasitic nematodes. While biocidal treatments can detect general and specific soil suppressivenees, soil transfer studies by definition, apply only to specific soil suppressiveness. Finally, potential strategies to exploit suppressive soils are presented.

To the News Service home page