Spectroscopic imaging reveals early changes leading to breast tumors

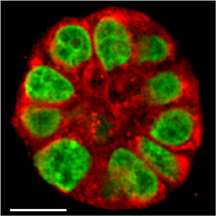

This image shows a live human mammary gland structure created in research that uses a new imaging technology to reveal subtle changes in breast tissue, representing a potential tool to determine a woman's risk of developing breast cancer and to study ways of preventing the disease. Unlike conventional cell cultures, the 3-D cultures have the round shape of milk-producing glands and behave like real tissue. (Purdue University image/Shuhua Yue)

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – Purdue University researchers have created a new imaging technology that reveals subtle changes in breast tissue, representing a potential tool to determine a woman's risk of developing breast cancer and to study ways of preventing the disease.

The researchers, using a special "3-D culture" that mimics living mammary gland tissue, also showed that a fatty acid found in some foods influences this early precancerous stage. Unlike conventional cell cultures, which are flat, the 3-D cultures have the round shape of milk-producing glands and behave like real tissue, said Sophie Lelièvre (pronounced Le-LEE-YEA-vre), an associate professor of basic medical sciences.

Researchers are studying changes that take place in epithelial cells, which make up tissues and organs where 90 percent of cancers occur. The changes in breast tissue are thought to be necessary for tumors to form, she said.

"By mimicking the early stage conducive to tumors and using a new imaging tool, our goal is to be able to measure this change and then take steps to prevent it," Lelièvre said.

The new imaging technique, called vibrational spectral microscopy, can be used to identify and track certain molecules by measuring their vibration with a laser. Whereas other imaging tools may take days to get results, the new method works at high speed, enabling researchers to measure changes in real time in live tissue, said Ji-Xin Cheng, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and chemistry.

By monitoring the same 3-D culture before and after exposure to certain risk factors, the new method enables researchers to detect subtle changes in single live cells, he said.

Findings are detailed in a research paper appearing this week in the Biophysical Journal. The paper was written by doctoral students Shuhua Yue, Juan Manuel Cárdenas-Mora, and Lesley S. Chaboub, Lelièvre and Cheng.

"This work shows the importance of engineering for the development of primary prevention research in breast cancer," said Yue, a biomedical engineering student whose work was funded through a fellowship from the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program.

The research is part of the International Breast Cancer and Nutrition (IBCN) project launched by Purdue in October 2010 to better understand the role nutrients and other environmental factors play in breast tissue alterations and cancer development.

Researchers studied live tissue in a culture that reproduces the mammary epithelium.

"This extremely sensitive technique shows the harmful impact of a nutrient called arachidonic acid," said Lelièvre, associate director of Discovery Groups at the Purdue Center for Cancer Research. "This fatty acid has been previously proposed to increase breast cancer risk, but until now there was no biological evidence of what it could do to alter breast epithelial cells."

The imaging method detects changes in the "basoapical polarity" of epithelial tissues. Specific proteins and other biochemical compounds called lipids are normally located in one of two regions, called the basal and apical membranes. Because only certain proteins and lipids are found in basal membranes, while others are located only in apical membranes, the cells are said to be polarized.

"This polarity is critical for the proper structure and function of tissue," Lelièvre said. "What we have shown previously is that when polarity is altered, tissue that otherwise looks normal can be pushed into a cell cycle necessary to form a tumor. It's the earliest change in the epithelial tissue that puts the cells at risk to form a tumor. Now, thanks to the vibrational spectral microscopy technique developed by Dr. Cheng, we can measure apical polarity status in live tissues and real time."

The findings could lead to a method for preventing tumor formation by restoring the proper polarity.

"We are mimicking formation of breast epithelium as it is normally polarized, and we can play with it and make it lose apical polarity on demand," Lelièvre said. "Then we can mimic an early change thought to be conducive to tumor development."

The researchers aim to use the imaging technology on live 3-D cultures of noncancerous breast tissue to screen for protective and risk factors for breast cancer the same way that tumors are used now in cultures to screen for drugs that can be used for treatment.

"Now there is no good way to assess risk for breast cancer," Lelièvre said. "Assessments are mainly based on family history and genetic changes, and this only accounts for a very small percentage of women who get breast cancer. We need technologies to assess the risk better and then screen for protective factors that could be used on individual patients because not everybody will be responsive to the same factors."

The National Cancer Institute estimates that in the United States in 2009 more than 192,000 women were diagnosed with breast cancer and more than 40,000 women died of the disease.

An immediate application of the technique is a way to study cell lines created from tissue taken from women at different risk levels, screening for factors that could restore full polarity in the breast tissue to prevent tumor formation.

"The state of the art is to take tumor cells, put them in a 3-D culture where they form tumors, and then test drugs on these tumors," Lelièvre said. "What we want to do now is the same thing but for preventive strategies using a normal tissue."

In a collaboration with researchers at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, the team plans to study cell lines from women who are at different risk levels.

The new imaging tool was needed because conventional live cell imaging methods are designed for flat cell cultures. Mimicking tissue polarity requires a 3-D culture to form the mammary gland structures at the end of the breast ducts. The structures resemble tiny balls about 30 microns in diameter and contain about 35 cells.

Cheng said his lab will continue to develop a "hyperspectral" imaging system capable of not only imaging a specific point in a culture but also many locations to form a point-by-point map so that tissue polarity can be directly visualized.

This work was supported by a Showalter grant, the National Institutes of Health, Komen for the Cure, a Congressionally Directed Medical Research/Breast Cancer Research Program Predoctoral Traineeship, National Cancer Institute, Cancer Prevention Internship Program administered by the Oncological Sciences Center and Discovery Learning Research Center at Purdue's Discovery Park, and an Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute Career Development Award.

Writer: Emil Venere, 765-494-3470, venere@purdue.edu

Sources: Sophie Lelièvre, 765-496-7793, lelievre@purdue.edu

Ji-Xin Cheng, 765-494-4335, jcheng@purdue.edu

Related websites:

Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering

Department of Basic Medical Sciences

News release about International Breast Cancer and Nutrition Project

ABSTRACT

Label-Free Analysis of Breast Tissue Polarity by Raman Imaging of Lipid Phase

Shuhua Yue,† Juan Manuel Cárdenas-Mora,‡ Lesley S. Chaboub,‡ Sophie A Lelièvre,‡�* and Ji-Xin Cheng†�*

†Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, ‡Department of Basic Medical Sciences, and �Center for Cancer Research, Purdue University

The formation of the basoapical polarity axis in epithelia is critical for maintaining the homeostasis of differentiated tissues. Factors that influence cancer development notoriously affect tissue organization. Apical polarity appears as a specific tissue feature that, once disrupted, would facilitate the onset of mammary tumors. Thus, developing means to rapidly measure apical polarity alterations would greatly favor screening for factors that endanger the breast epithelium. A Raman scattering-based platform was used for label-free determination of apical polarity in live breast glandular structures (acini) produced in three-dimensional cell culture. The coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering signal permitted the visualization of the apical and basal surfaces of an acinus. Raman microspectroscopy subsequently revealed that polarized acini lipids were more ordered at the apical membranes compared to basal membranes, and that an inverse situation occurred in acini that lost apical polarity upon treatment with Ca2þ -chelator EGTA. This method overcame variation between different cultures by tracking the status of apical polarity longitudinally for the same acini. Therefore, the disruption of apical polarity by a dietary breast cancer risk factor, u6 fatty acid, could be observed with this method, even when the effect was too moderate to permit a conclusive assessment by the traditional immunostaining method.