Collider achieves world record; Purdue researchers part of experiment

Shown is an event display from one of the recorded collisions of the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment. The yellow lines are tracks made by individual charged particles emanating from the collision and recorded by the Purdue-designed silicon camera. The red line (bottom right) is produced by a muon, a fundamental particle that is a heavy cousin of the electron. The red and blue plot-like structures are the response of another specialized camera that measures energy. Purdue was involved in building all three of these cameras.

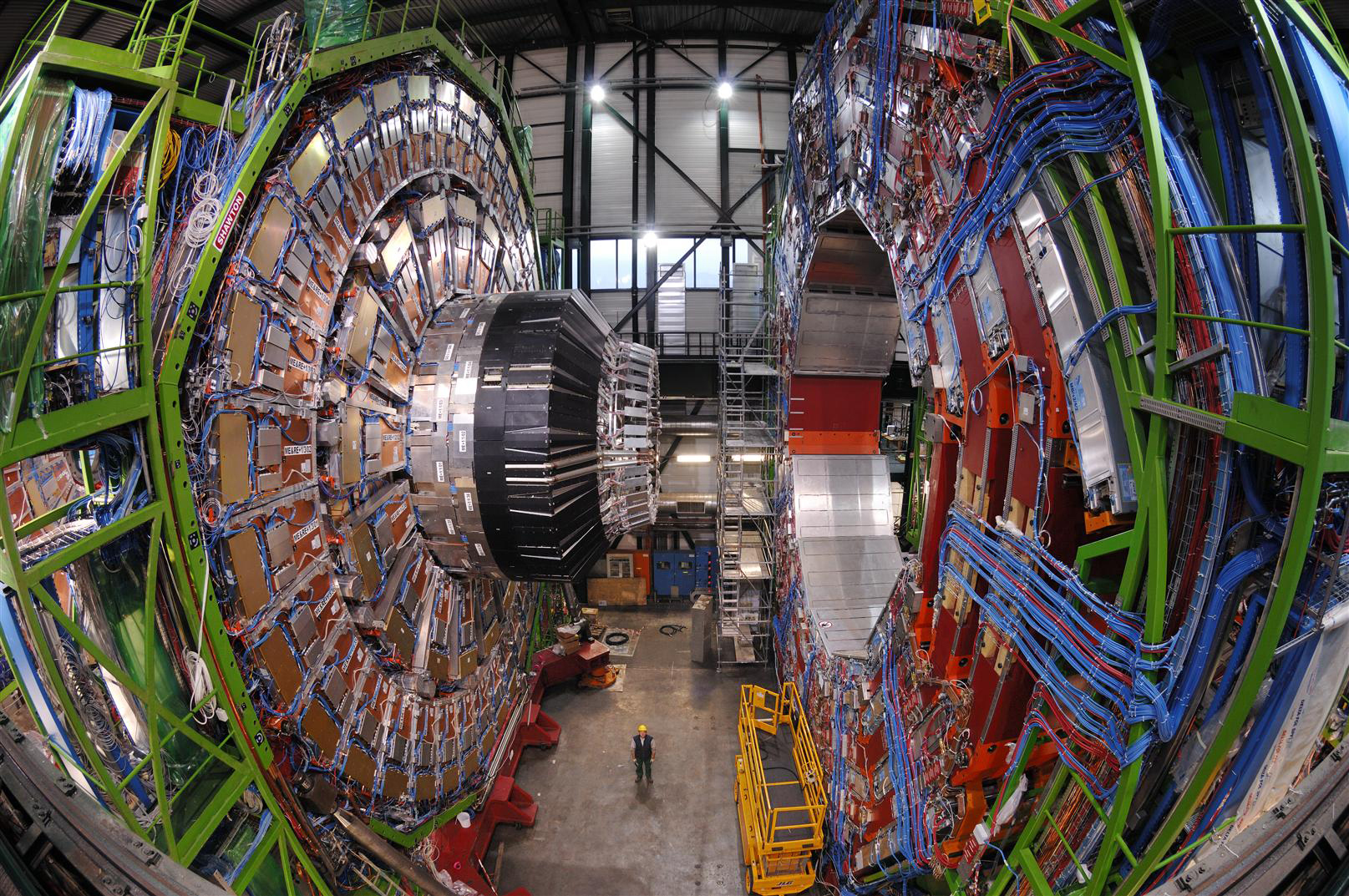

On Tuesday (March 30) particle beams reached an energy of 7 trillion electron volts, smashing protons together with three times more energy than had ever before been achieved, during an experiment using the world's largest particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland.

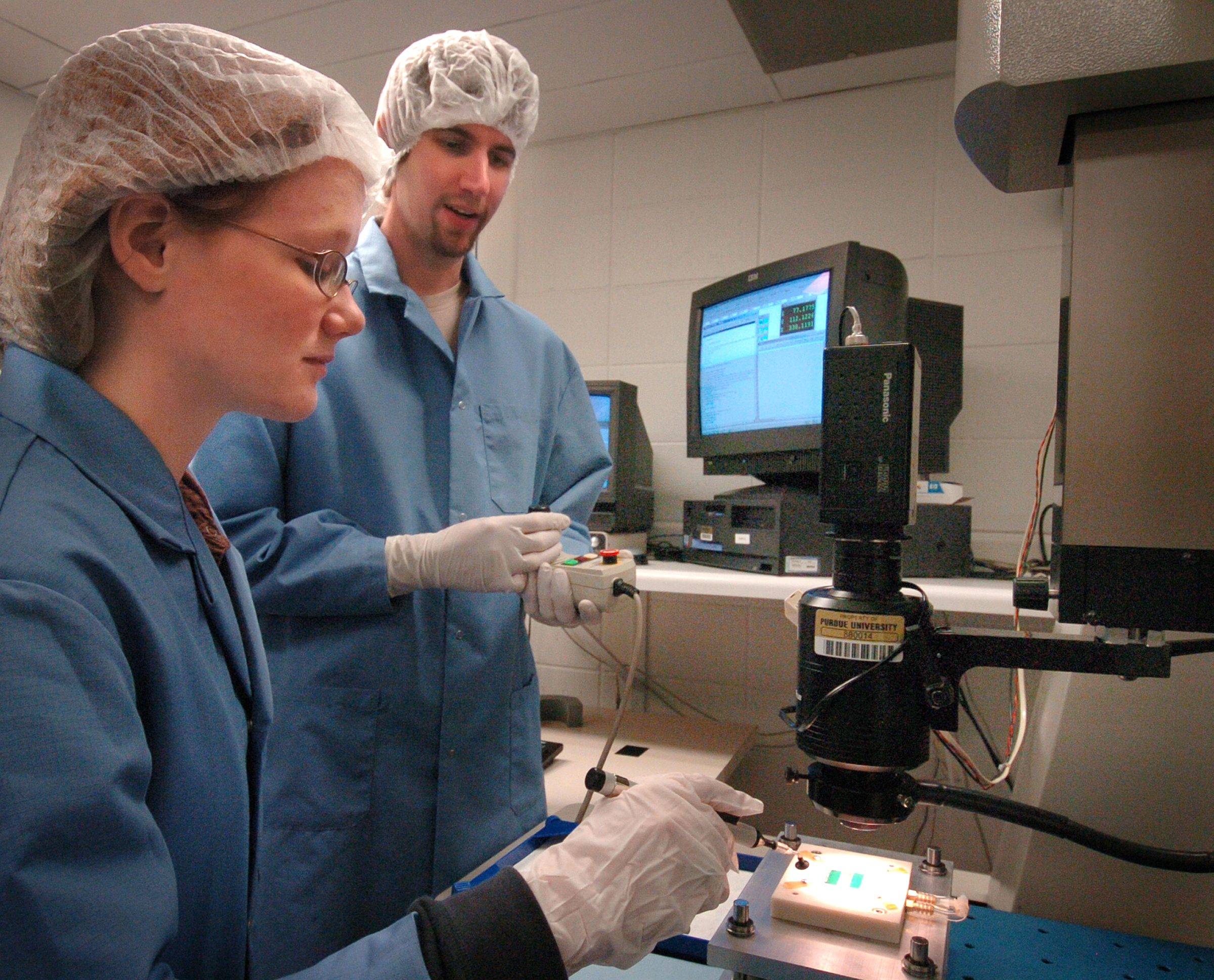

Purdue teams spent more than eight years working on equipment for the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment, which is currently running at the collider. Purdue's work included designing and building special cameras, called pixel detectors, used to capture images of the tiny particles that result when two protons collide.

Purdue physics professors Daniela Bortoletto, the Edward Purcell Distinguished Professor of Physics, and Ian Shipsey, the Julian Schwinger Distinguished Professor of Physics, led the camera design and assembly teams, respectively.

Purdue undergraduate students Emily Grace and Brian Kozak help build a camera that may soon glimpse dark matter, the formation of black holes and Higgs particles at the Large Hadron Collider. (Purdue University file photo/David Umberger)

"The Large Hadron Collider will recreate the primordial soup of the universe when it was just a picosecond old," said Bortoletto, who also is U.S. coordinator of the CMS experiment. "From studying it we may come to know how our universe was born, how it will evolve and how it will end."

Shipsey, who also is the co-coordinator of the LHC Physics Center at Fermilab, said the experiments also may reveal the nature of dark matter, which is thought to hold galaxies together, and whether there are spatial dimensions beyond the three known to exist.

"These experiments promise to be as revolutionary as when Galileo turned his telescope to the sky in 1608," Shipsey said. "In the years ahead we hope to reveal the origins of the most basic property of matter - mass - without which there would be no atoms and no life as we know it."

Basic discoveries in particle physics have led to important tools for our health and quality of life, he said.

"Great technological breakthroughs, like the Large Hadron Collider, lead not only to great discoveries, but also to revolutionary applications," Shipsey said. "I expect that the technologies developed for these experiments and the accelerator will give rise to new inventions that will change our way of life as much as other applications that stemmed from particle physics, such as the World Wide Web and the use of accelerators to produce intense X-ray beams used in materials science, biology, chemistry, the study of DNA, pharmaceutical research, and in medical imaging and the treatment of cancer."

In addition to Bortoletto and Shipsey, Purdue professors Virgil Barnes, Art Garfinkel, Laszlo Gutay, Matthew Jones, David Miller and Norbert Neumeister were part of the international team that built the compact muon solenoid. Purdue's information technology group also is contributing to the global distributed computing system that is now analyzing the collisions. The Purdue teams collaborated with Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory and other U.S. and European universities to complete the project.

Writer: Elizabeth Gardner, 765-494-2081, ekgardner@purdue.edu

Sources: Daniela Bortoletto, 765-494-5197, Daniela@physics.purdue.edu

Ian Shipsey, 765-494-0706, shipsey@purdue.edu

Related news releases:

Purdue scientists, students help create a key piece of one of the world's most powerful cameras

Universities prepare as physicists plan to pop protons

World's largest particle accelerator goes live; Purdue Web site to share the action