Not to be Forgotten

HHS Researchers Strive to Improve Care, Develop Treatments for Dementia

Story by Elizabeth Gardner, photos by Charles Jischke

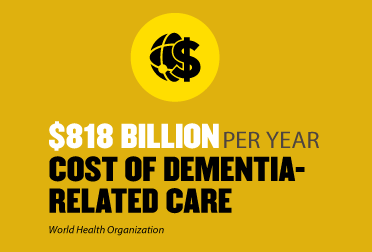

A new case of dementia is diagnosed every three seconds, according to the World Health Organization. Chances are you know someone whose life is touched by dementia, which is overwhelming physically, psychologically and economically for those who have it and also for their families and caregivers.

Dementia is a progressive deterioration in cognitive function that can affect memory, comprehension, learning capacity, language and judgment, and sometimes leads to personality changes. Damage to the brain from disease or stroke can lead to dementia, and some of the various forms include Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia. Currently, there is no known treatment to stop or reverse its course.

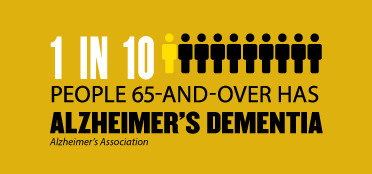

The risk of developing dementia increases with age, and a rising population of older individuals means a greater proportion of people will be touched by it. America’s 65-and-over population is projected to nearly double over the next three decades, from 48 million to 88 million by 2050, according to a 2015 report by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The global estimate for this population in 2050 is 1.6 billion, and the World Health Organization (WHO), a specialized agency of the United Nations, has made dementia a public health priority.

“The WHO has endorsed a global action plan with goals of improving the lives of people with dementia, their families and the people who care for them, while decreasing the impact of dementia on communities and countries,” says Richard Mattes, director of the Public Health Graduate Program at Purdue University. “Dementia poses a great challenge to individuals, but it also takes a broader toll on government and society, requiring support from the health, social, financial and legal systems. Action is needed to improve our quality of life as we age in terms of both our health and security.”

For decades, Purdue University researchers within the College of Health and Human Sciences have pursued improved care for those with dementia and worked to develop methods for earlier detection and potential treatments.

Defining a difference

Nancy Edwards, an associate professor of nursing, has been working with individuals who have dementia since first becoming a nurse’s aide more than 40 years ago. She received Sigma Theta Tau International’s 2015 Amy J. Berman Geriatric Nursing Leadership Award in recognition of her significant research contributions to the health care of older adults.

Edwards is currently working to differentiate by various types of dementia the needs of the caregivers and individuals with dementia. The project includes interviewing both patients and caregivers to hear directly from them the challenges they face and what needs are or are not being met with current treatment protocols.

“All dementia is not the same, and patients and caregivers have different needs depending on the type of dementia they face,” Edwards says. “The impact of dementia can span from an 80-year-old with memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease to a man in his 50s who lacks impulse control due to frontal temporal dementia to someone suffering from body-movement issues coupled with cognitive decline from Lewy bodies. Each of these individuals, their families and caregivers face unique pressures and difficulties, and the support and advice given need to reflect that.”

Edwards has focused on three common forms of dementia: Alzheimer’s, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia.

She has worked for 20 years to better communicate to nurses the classifications of the different forms of dementia and the most effective care for each type. She and her students use the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders to undergird the articles and presentations they create to educate the nursing and lay community.

Edwards’ goal is to help nurses who work with patients at risk for dementia spot early signs in order to make a timely referral, better recognize the characteristics of the different types, and offer care tailored to the individual and family. This should, in turn, improve the patient’s quality of life and avoid unnecessary hospitalizations or institutionalizations. She also wants to remind the community that caregivers need care themselves.

“There is a great need to give caregivers tools to manage behaviors that can be associated with the various dementias and provide caregivers support to cope with the social stigma and isolation they can feel in addition to the emotional toll of a sick loved-one,” she says. “This project isn’t directly funded, so for myself and my team it is a labor of love.”

Fish work swimmingly

Edwards has worked with Alan Beck, the Dorothy N. McAllister Professor of Animal Ecology and director of Purdue’s Center for the Human-Animal Bond, to explore the effect of animals on patients in long-term care settings. Previous research has shown animal therapy to reduce blood pressure, promote relaxation and stimulate the healing process.

“With the growing population of older adults and subsequent rise in the number of individuals with dementia, it is imperative that we find nonchemical, cost-efficient ways to mitigate the challenging behaviors that occur,” Edwards says. “It is better for the individuals with dementia and those who provide care for them.”

For patients with dementia, spending time with a dog has been shown to increase social interactions, as well as decrease agitation and yelling, screaming or abusive behavior toward staff, she says. However, there are challenges as both patients and dogs must be supervised and contact time is limited for dog therapy. This inspired Edwards and Beck to explore the benefits of therapy through other types of animals.

Their research indicated that the presence of an aquarium in a main activity/dining area improved dementia unit residents’ behaviors in the areas of cooperation, irrationality, sleep and inappropriate behaviors. The associated decrease in patients’ negative behaviors also led to a reduction in the stress expressed by the staff and to an increase in their job satisfaction, which is critical to preventing burnout, staff turnover and improving quality of care, Edwards says.

The Purdue researchers also found that an aquarium placed in view of the dining tables improved the food intake of individuals with dementia.

“People with dementia often have trouble getting adequate nutrition because they get distracted when it is time to eat,” Edwards says. “In our study, the feeding schedule of the fish was matched to the meal times of the residents, so that the fish would be active during the meals. Results showed it was both calming to those who would get agitated, as they would sit and watch the fish, and stimulating to those who were lethargic, as it captured their attention.”

This decreased the weight loss that is commonly seen in individuals with dementia, she says.

Next best thing to man’s best friend

Edwards and Beck also teamed with a psychologist and information science professors from the University of Washington to examine the use of a robotic dog, the Sony AIBO, as a potential companion for older and socially isolated adults. Although the study did not focus on individuals with dementia, Edwards believes the results could translate well to that group.

“A robotic dog isn’t harmed if someone forgets to feed it or take it outside, and it could be a better option than a live animal for someone who suffers from dementia,” she says. “The social and emotional benefits we’ve seen in animal therapy are there with the robotic dog too. It might not be as good as a live dog, but it is the next best thing.”

The study examined the influence of robotic dogs on depressive symptoms, morale and life satisfaction on older adults living in community residential settings. Of the 12 participants in the study, all said they talked with AIBO and that the dog was fun and entertaining; 10 participants said AIBO would be a good companion and that they confided in the robotic dog. When asked, “If you were alone in your room, would you feel better if AIBO was with you?” all 12 answered yes. All participants said they liked to talk with AIBO, hold and pet it and show it to others.

The results of the study indicated an improvement in life satisfaction and depressive symptoms and also suggested robotic-dog companionship led to increased socialization with other individuals, increased morale and increased physical activity, Edwards says.

“Having the unusual dog led to more conversations with other people, and the participants engaged in physical play with the dog,” she says. “I think it is a good option for those with a mobility issue, who live in areas that prohibit dogs, or who have dementia and perhaps can’t handle a living dog or animal, but who are interested in this type of therapy.”

Heavy metal research

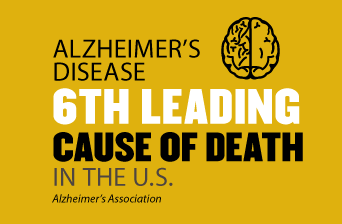

Wei Zheng, professor and former head of Purdue’s School of Health Sciences and fellow of the Academy of Toxicological Sciences, has been studying Alzheimer’s disease for 15 years. Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60 to 80 percent of all cases. Zheng leads teams of scientists on projects pursuing biomarkers, identification of increased risk factors and potential treatments.

This summer the National Institutes of Health awarded a team led by Zheng $2.3 million to pursue research that could help develop new strategies for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s.

The project builds on the correlation between the damaged blood-brain barrier system and increased incidence of Alzheimer’s disease to investigate the processes that lead to the disease. Exposure to lead, a toxic heavy metal, is one known cause of such damage.

Accumulation of a protein called beta-amyloid is known to foster the development of senile plaques in the brain typical of a person with Alzheimer’s. However, scientists do not know for certain how beta-amyloid is deposited in the brain, Zheng says.

“By looking into the molecular mechanisms that lead to an accumulation of beta-amyloid and, in turn, the development of senile plaques, we hope to find a way to stop Alzheimer’s disease in its tracks,” Zheng says. “We hope to prove our theory that compromised structure and function of the blood-brain barrier system, for example owing to exposure to the toxic metal lead in our daily life, may increase levels of beta-amyloid in the brain. That, in turn, leads to the buildup of senile plaques.”

Zheng and his colleagues focus on changes to the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, which controls the transport of molecules to and from the brain, after lead exposure. They theorize that these changes are key to Alzheimer’s disease onset, development and progression.

“Our theory is that exposure to lead damages the tiny blood vessels embedded in brain tissue in ways that allow more beta-amyloid in and also hinder the barrier’s ability to take it back out of the brain,” Zheng says. “If a blood vessel is damaged, it may leak and allow contact between brain cells and molecules previously kept out. A damaged blood vessel also reduces the blood flow to that area, such that normal cleanup mechanisms aren’t available. This progressively causes trouble.”

Through the NIH-funded project, Zheng’s team hopes to establish the relationship between lead exposure and changes in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier to beta-amyloid and to show that the barrier and blood vessels play a key role in regulating lead-induced beta-amyloid plaques in the brain.

Wine, exercise and chess

“Lead exposure and its correlation to Alzheimer’s disease development is in itself a significant problem, as those born in the sixties and seventies have likely been exposed through leaded gasoline – the prevalence of Alzheimer’s among this group of Americans is estimated to be between 8.4 and 13.8 million in the next several decades,” Zheng says. “But if we can understand the specifics of how lead acts on the body and what changes trigger the path to Alzheimer’s, it will not only give us a better understanding of the disease in general, but also allow us to find potential targets for treatment.”

If blood circulation within the smallest blood vessels in the vasculature of the brain is key, it could explain why certain activities have been correlated with a decrease in risk of dementia, Zheng says.

“Exercising, drinking wine and playing chess all increase microcirculation in the brain at the time of the activity, which could maintain the health of blood-brain barriers and increase the rate of removal of beta-amyloid,” he says.

Few studies have been done on the role of the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease development and progression, Zheng says.

“If the microcirculation is indeed critical, it offers the potential for early intervention,” he says. “Perhaps a diet to improve cardiovascular health and therapies to improve local brain microcirculation could help prevent Alzheimer’s.”

Future findings

Zheng and his collaborator Yansheng Du at Indiana University School of Medicine designed an antibody therapy approach that has been shown in the blood-brain barrier model to pull beta-amyloid protein from cerebral spinal fluid and return it to general circulation. The team plans to extend the experiment to animal models with Alzheimer’s disease, he says.

“Beta-amyloid has no known function in the brain, and the hope is that it could be removed without causing any harmful side effects,” Zheng says. “Although this wouldn’t be able to reverse any existing plaques, it could greatly slow or halt their progression.”

The team also is investigating whether or not there is a correlation between a high concentration of lead found in one’s bones and the development of Alzheimer’s.

Zheng works with Linda Nie, a health physicist and associate professor in the School of Health Sciences at Purdue, to measure lead accumulation in bones and compare it with changes in the brain. The team uses a hand-held detection device based on the ability to identify lead concentrations through an X-ray fluorescence technique.

“Perhaps lead deposition in bone could be linked to amyloid accumulation in the brain,” Zheng says. “A noninvasive scan of a bone could then be used to assess risk for development of the disease.”

Early experience

Both Zheng and Edwards point to the importance of meeting with the individuals who suffer from the disease and the families and communities affected by it.

“It is very important as a researcher to get out of the lab and meet the patients your work could benefit,” Zheng says. “I encourage my students to do this as well, so that they know their work is not isolated from the rest of the world — that they can make a difference in the world. That is the heart of any public health program. They need to see the real value of what they are doing and whom they may help.”

Before her career began, Edwards helped elderly neighbors as a child.

“I was raised to respect and assist our elderly neighbors who needed help, and it was wonderful to interact with them and enjoy the stories they shared,” she says. “When I worked with patients, and in my research today, I think of how I would want to be treated or how I want my parents to be treated. That is my motivation. We must remember to treat these people with the dignity we all deserve.”

More Life 360 Stories

Alumni

- Outdoor Learning Space

- A Fond Farewell

- Lessons From Those Who Live the Longest

- HTM Professor Leads Global Trend in Advancing Sustainable Tourism

- Convenience, Health Fuel Growth in Boxed-Food Delivery Industry

- Defining the Field for 80 Years

- Compassion Comes Full Circle

- Purdue Memorial Union Inspired Houston-Based Restaurateur

- Where are they now?

Faculty

- Outdoor Learning Space

- A Fond Farewell

- Tips for Aging Well

- Developing a Child Care Curriculum for the Department of Defense

- Not to be Forgotten

- HTM Professor Leads Global Trend in Advancing Sustainable Tourism

- Convenience, Health Fuel Growth in Boxed-Food Delivery Industry

- Better Beginnings

- Defining the Field for 80 Years

- MRI Facility Opening New Avenues of Research